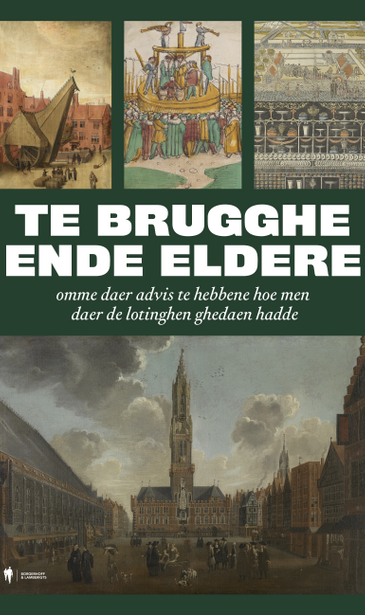

The idea quickly caught on. Other cities, always looking for new sources of income, copied Bruges' example. This happened first in the immediate vicinity, in other cities in the Burgundian Netherlands: Sluis, Ieper, Ghent, Lille, Nieuwpoort, Oudenaarde, Antwerp, Leuven... Between 1441 and 1500, at least 82 lotteries were organised in the Low Countries (the majority still in Bruges, but from the sixteenth century, the focus shifted to Antwerp). Lotteries also appeared in Germany from 1470 onwards, and it was the lotteries in Rome, Genoa and Venice which made the Italian word "lotto" - derived, like "lottery", from the Dutch word "lot", chance - the internationally recognisable brand name from 1504 onwards. As such, the lottery followed the path of the trade routes of the time, from the Netherlands through Germany to northern Italy. By the sixteenth century they were popping up all over Europe.

The organiser’s aim, usually a city but sometimes also a private organisation, was obviously to make a profit. But this was used to finance collective needs: strengthening the city walls, building a hospital or a church, or paying off debts, as in the case of that first draw in 1441. This social aspect is still an essential feature of a lottery too. In 2020, the National Lottery of Belgium provided support worth 185,300,000 euros, for numerous projects and associations with a humanitarian, social, sporting, cultural and scientific purpose.

Author: TOM NAEGELS

Stadsarchief Brugge-sq.png)

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.png)

Phoebus Foundation(2).png)

Sint-Sebastiaansgilde Brugge(2).png)

Jan Darthet-2.jpg)